commentarY

Just Say Nothing

As we approach the midpoint of the Hebrew month of Elul, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur draw near, ushering in the Days of Awe. In about a month from now, as the sun sets, the reverberating melody and contemplative words of Kol Nidre will resonate through synagogues worldwide.

Parashat Ki Tetse, Deuteronomy 21:10 – 25:19

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

As we approach the midpoint of the Hebrew month of Elul, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur draw near, ushering in the Days of Awe, or Yamim Nora’im. In about a month from now, as the sun sets, the reverberating melody and contemplative words of Kol Nidre will resonate through synagogues worldwide. Kol Nidre, which translates to “all vows,” holds the peculiar function of preemptively absolving the binding nature of future promises for the upcoming year. At first glance, this prayer might be interpreted as either laziness or a spiritually questionable way to evade responsibility.

Interestingly, Kol Nidre seems to stand in direct contradiction to a proclamation found in this week’s Torah portion: “If you had refrained from making a vow, no guilt would have come upon you” (Deut 23:23). The words of the wise preacher Koheleth, traditionally attributed to King Solomon, echo this sentiment: “It is better that you do not make a vow than you make a vow and not fulfill it” (Eccl 5:4). Furthermore, the rabbis went as far as to emphatically warn against delaying vows, linking this procrastination to idolatry, unchastity, bloodshed, and slander (Leviticus Rabbah 37).

To reconcile this apparent contradiction, it’s essential to understand that not all vows are created equal in Judaism. There are distinct categories of vows, including oaths made as witnesses in court, purification oaths for debtors, personal obligations before God, and solemn affirmations to enhance credibility. However, none of these categories of vows are eradicated by mere ritual; the individual remains accountable for these vows legally, ethically, relationally, and religiously. The exception might be the personal aggrandizement type of vow, which could provide insight into the rationale behind Kol Nidre’s preemptive nullification of oaths.

But first, let’s delve into the origins and lore of Kol Nidre. Although its inception remains veiled in mystery, theories about its genesis abound. One prominent theory links the prayer’s wording to the predicament faced by Spanish Jews during the Inquisition in the 15th century.

The alternative of forced conversions to Christianity or death pushed many Jews to secretly practice Judaism at home. Kol Nidre could have emerged to nullify their coerced conversion vows before God. Most scholars, however, trace Kol Nidre back even further, possibly to the contracts of the Babylonian Jewish community during the 6th and 7th centuries. Despite differing origins, the consensus remains those vows made under duress, or the threat of death are not upheld by the Divine, and therefore, neither should we consider these binding.

This notion of vows made under extreme pressure dovetails with ethical considerations propagated by historical figures like Augustine and Emmanuel Kant. The Church Father Augustine (356–430 CE) argued, “Does he not speak most perversely who says that one person must die spiritually so that another may live? . . . Since, then, eternal life is lost by lying, a lie may never be told for the preservation of the temporal life of another.” Kant, an 18th century Christian philosopher, took a similar position. Both grappled with the moral dilemma of lying to safeguard lives.

In contrast, Judaism underscores that truth is a tangible interpersonal event, not just an abstract principle. The Torah illustrates instances where lying to preserve life is permissible. The rabbis understood the Torah to teach that for the preservation of life even God instructs the prophet Samuel to tell a lie (1 Sam 16:1–2). The rabbinic formula is “great is peace, because for its sake God altered what Samuel was to say.” This is applicable to those who concealed Jews during the Holocaust. In this case a false testimony is the same as a broken oath, but justifiable for the sake of pikuach nefesh, the preservation of life. Hence, Judaism honors those who lied to protect lives from the atrocities of the Nazis.

Moving beyond the quandaries of when vows should be nullified, it’s worth examining the most superfluous of oaths. This pertains to the category of vows made to enhance one’s credibility and status—a practice that both Yeshua and the rabbinic tradition scrutinized. Early rabbinic thought frowned upon invoking the Divine Name, adhering to the commandment, “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain” (Exod 20:7). This extends to avoiding actions that exploit divine authority for personal gain.

People began using circumlocutions like “the Merciful One” or “the Forbearing One” in their oaths, later resorting to phrases like “by heaven,” “by the Temple,” or “by the covenant.” Yeshua, however, disapproved of these formulations as well, as they still sought to circumvent divine sovereignty. His perspective concurred with the rabbinic stance against unnecessary vows.

Given these contexts, why, then, do we continue to proclaim Kol Nidre, nullifying all future vows from “this Yom Kippur until next Yom Kippur”? At face value, it seems paradoxical to accept the words of someone who has already absolved themselves of responsibility. In modern language, phrases like “I’m not lying” have become commonplace. Thus, a culture of swearing leads to the depreciation of trust in speech, dividing it into two categories: unconditionally true by Divine affirmation and others that appear relatively true or merely plausible. Nullifying all vows proactively admits the fragility of our commitment while elevating the sanctity of truth-telling. Those who grasp this concept tend to exercise caution in their speech; discretion is affirmed through silence, and actions resonate louder than words.

Just as the commandment against killing and slander emphasizes the sanctity of human life, and the preservation of marriage sanctifies the family as society’s fundamental unit, refraining from unnecessary swearing underscores truth as the bedrock of the Torah way of life—the foundation of the Kingdom of God.

Justice, Not Vengeance

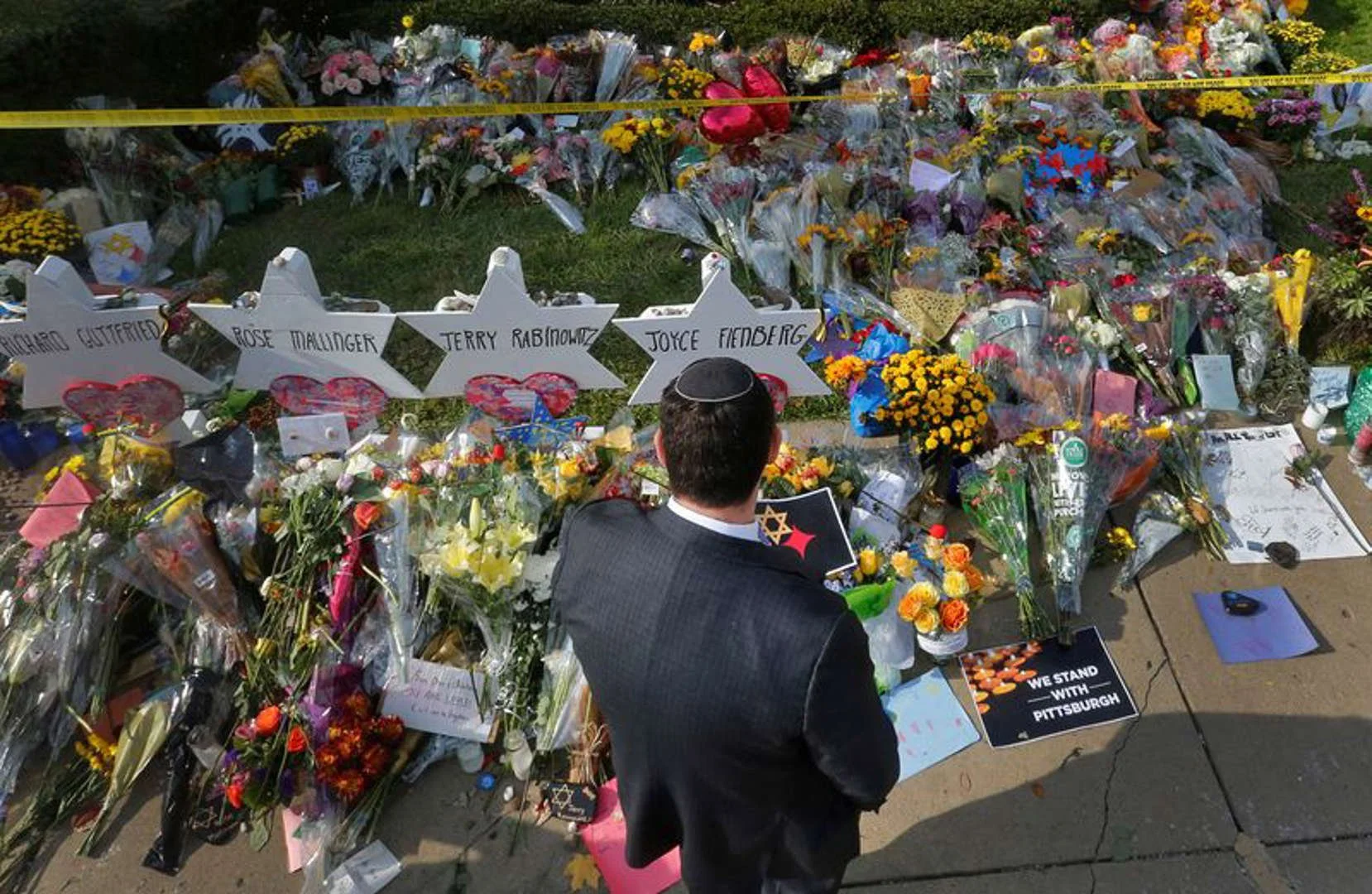

On October 27, 2018, Robert Bowers entered the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh shouting “All Jews must die!” He then proceeded to open fire. After the chaos had settled, eleven people had been murdered and six more critically wounded. It is the most violent antisemitic attack ever perpetrated on American soil.

Parashat Shoftim, Deuteronomy 16:18 - 21:9

Matthew Absolon, Beth Tfilah, Hollywood, FL

Justice, and only justice, you shall follow, that you may live and inherit the land that the Lord your God is giving you. (Deut 16:20)

The man who acts presumptuously by not obeying the priest who stands to minister there before the Lord your God, or the judge, that man shall die. So you shall purge the evil from Israel. ( Deut 17:12)

On October 27, 2018, Robert Bowers entered the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh shouting “All Jews must die!” He then proceeded to open fire. After the chaos had settled, eleven people had been murdered and six more critically wounded. It is the most violent antisemitic attack ever perpetrated on American soil.

Nearly five long years later on August 3, 2023, Bowers was formally sentenced to death.

Why did it take so long to exact justice? When we have the videos, the confessions, the 911 calls, the many, many eye-witnesses; why should vengeance be delayed for such an agonizingly long time? Why should the victims and the surviving families suffer so long to be denied their vengeance?

The answer is that we in America do not believe in vengeance, we believe in justice; and this belief finds its roots in the biblical world view of justice.

Rabbi Uri Regev in his paper, “Justice and Power: a Jewish Perspective” (https://www.berghahnjournals.com/view/journals/european-judaism/40/1/ej400113.xml) suggests that the Jewish fixation on justice starts at the very beginning of the Jewish story with our father Abraham. God commends Abraham in this way:

For I have chosen him, that he may command his children and his household after him to keep the way of the Lord by doing righteousness and justice, so that the Lord may bring to Abraham what he has promised him. (Gen 18:19)

Here the words “righteousness and justice” – tzedakah u’mishpat – stand as the cornerstone of Jewish law and indeed are the vehicle through which the Lord will “bring to Abraham what he has promised him.” Stated another way, Abraham will receive God’s promises “by doing righteousness and justice.”

Justice, however, can be a pesky thing. It is not convenient, and it stands as a barrier to our fits of anger, rage, and vengeance. Justice is often described as having “slow turning wheels” or, in the words of Martin Luther King Jr., “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Vengeance, however, requires no self-control; no moral discipline; no pause for thought. Vengeance amplifies its thirst for blood, when working in the collective of the mob. As we look down the annals of history, and reflect upon the social upheavals of the modern day, we see the great dangers of mob rule. Beckoning to the primitive and devilish ways that lurk in the deep recesses of each of our hearts, mob justice froths at the mouth in a sort of bestial trance, that defies reason, discipline, and self-control.

Our Lord was well accustomed to the mob. The mob tried to toss him off the cliff. He saved the woman caught in adultery from the mob. He was traded for the terrorist Barabbas by the approval of the mob.

Justice, in contrast, is a discipline. And moreover it cannot be explained outside a transcendent worldview. Without God, there is no framework to define justice. In fact, physical justice only has power when aligned with the spiritual view that man is made in the image of God (Gen 1:27; 9:6). As such man is endowed with free moral agency, and simultaneously endowed with infinite individual worth.

And so we see that justice at its core is not a system, or a person, or a socio-cultural phenomenon; justice is an outward expression of faith. It is an unwavering belief that man is created in the image of the Almighty God. As such we all contain the divine spark with its infinite and intrinsic value.

The neurotic hand of vengeance pays no attention to God’s claim upon every living soul and, when brandished in haste, vengeance leads to vengeance, and blood to more blood. Vengeance, like Justice, is a choice. It is a decision that we enter into for our own hurt.

Justice is a fruit that is cultivated in the individual heart as a moral decision that we must make, as an expression of God’s character and in humble submission to his divine claim as creator of mankind.

We Jews, along with our faithful friends, all breathed a mournful sigh of relief as we heard the verdict upon Robert Bowers that August night. But more than that, we decided to reject vengeance. Although we were killed, we burned with righteous anger, our hearts were broken with hurt; we did not give way to vengeance. We did not riot in the streets; we did not loot our neighbors; we did not burn down the city square.

No. Instead, with discipline and dignity, we upheld our spiritual duty by “doing righteousness and justice” that the promises of God may be visited upon the Children of Abraham.

In parallel to this, we submitted to God’s divine claim as creator by affording Robert Bowers the dignity of divine worth, through the exercise of justice, in contrast to the neurotic hand of vengeance. A dignity that he did not afford to us.

Justice is an act of spiritual discipline. It stands as the calming and stable hand of God, against the neurotic hand of vengeance. Justice is not found in the chants of the mob, or the passions of the grieving, or the swift bullet of the lawman; justice is found in the individual heart of every person who recognizes God’s sovereignty over his creation.

“Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” Amen.

Scripture references are from the English Standard Version (ESV).

Freer Than We Think

Our parasha begins with Moses speaking to the people of Israel in the plains across the Jordan river, offering us what is clearly a choice. Note the opening word, Re’eh, “See.” We are not to offhandedly choose one way or another by default, but are to really see this choice, to deeply encounter it . . . even if we may not have previously recognized it as a choice.

Parashat Re’eh, Deuteronomy 11:26-16:17

Dave Nichol, Ruach Israel, Needham, MA

“See, I am setting before you today a blessing and a curse—the blessing, if you listen to the mitzvot of Adonai your God that I am commanding you today, but the curse, if you do not listen to the mitzvot of Adonai your God, but turn from the way I am commanding you today, to go after other gods you have not known.” (Deut 11:26-28 TLV)

So our parasha begins, with Moses speaking to the people of Israel in the plains across the Jordan river, offering us what is clearly a choice. Note the opening word, Re’eh, “See.” We are not to offhandedly choose one way or another by default, but are to really see this choice, to deeply encounter it . . . even if we may not have previously recognized it as a choice.

The concept of free will has taken a beating in recent years. An article in The Atlantic announces, for example, that “there’s no such thing as free will,” based on a growing body of research in neuroscience and evolutionary biology. This reflects a growing trend—in both the hard sciences and philosophy—of skepticism in our ability to freely choose, well, anything (of course, there is lively debate on this issue, which I won’t get into here). On the other hand, by opening this speech with the command to see, Moses seems to be teaching us the opposite message: we often have more freedom than we think, choices that we don’t even realize are choices.

As the Atlantic article argues, some choices may be predetermined by our subconscious or by habituation—which clothes to wear, which route to take to work, and what overpriced coffee to order at Starbucks. But then there are others we may not recognize: when we choose to interpret someone else’s actions charitably or with cynicism, or choose frustration over forbearance when faced with a whining child. But these are choices as well, even if we don’t usually see them as such.

Put another way, breaking into that bag of chips, reacting in anger when someone cuts us off in traffic, or jumping to conclusions about another person based on a first impression, are all choices, but only if we are aware of the choice and put in the work to claw back the freedom to make them.

Danny Silk, in his insightful book, Keep Your Love On! Connection, Communication & Boundaries, sees exercising this freedom as an essential ingredient in relationships:

If you want to preserve relationships, then you must learn to respond instead of react to fear and pain. Responding does not come naturally. You can react without thinking, but you cannot respond without training your mind to think, your will to choose, and your body to obey. It is precisely this training that brings the best qualities in human beings—like courage, empathy, reason, compassion, justice, and generosity—to the surface. The ability to exercise these qualities and respond gives you other options besides disconnection in the face of relational pain.

If you have spent time around children (or perhaps have been one yourself), you have probably heard logic along the lines of, “He did this to me, so I had to respond this way.” Actually, you’ve probably heard adults doing this (and, dare I say, done it yourself): rationalizing a response by appealing to the circumstances or actions of someone else. Silk doesn’t let us get off that easily:

Powerful people are not slaves to their instincts. Powerful people can respond with love in the face of pain and fear. This “response-ability” is essential to building healthy relationships.

It is exactly the freedom to not respond in a predetermined way that makes us human. The ability to say, “Wow, that hurt. I’m angry. I feel a deep need to respond in kind, but I choose not to,” is the moral achievement par excellence in Judaism: overcoming the yetzer hara (evil inclination) and mastering the nefesh habehamit (animal soul). Yeshua exemplifies this, in that his ultimate act was to respond to hatred, violence, and injustice with lovingkindness and self-sacrifice. In exercising freedom to respond with generosity one could say he was the ultimate human. This explains why the besorah narratives never present Yeshua’s actions as predetermined, but show him having a choice (in the desert, in the garden) and choosing rightly.

It is commonly said that our emotions are outside our control, and to an extent that’s true. But if we dig into them a little deeper, we may find that our reactions are often rooted in deeply-ingrained beliefs that are either untrue or only partially true. This is why our reactions sometimes feel necessary in the moment, and silly a few hours later. Similarly, we are pretty good at giving ourselves (or our friends) the benefit of the doubt. Someone who cuts us off in traffic is a jerk or a bad driver; if we do it ourselves, it’s simply because we had to get over. Sorry!

The truth is that we make decisions almost every minute of the day, and most of them are about how to perceive, rather than what to do. Even how we see and interpret the world has an element of choice in it. As one of my favorite bumper stickers says, “Don’t believe everything you think!” Our tradition is quite aware, as the social sciences continue to confirm, that humans are anything but purely rational beings.

But, rather than being a downer, this message is deeply empowering. Moses teaches us that as we enter the land we have this power of choice within us. We are not mere puppets of our genetics, environment, or culture. Far from it! With a little work, even our previous choices can be repudiated and rectified through teshuva.

The challenge for us is one of awareness: to hold off before reacting, and to see the forces inside us that lead us to interpret something one way versus another. Thus may we be free to choose the blessing set before us.

Don’t Forget How to Remember

Remembering and not forgetting is a major issue in life as it is in this week’s parasha. In our very first verses we read. “Because you are listening to these rules, keeping and obeying them, Adonai your God will keep with you the covenant and mercy that he swore to your ancestors.”

Parashat Ekev, Deuteronomy 7:12–11:25

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann, Ahavat Zion Messianic Synagogue, Los Angeles

Remembering and not forgetting is a major issue in life, as it is in this week’s parasha.

In our very first verses we read. “Because you are listening to these rules, keeping and obeying them, Adonai your God will keep with you the covenant and mercy that he swore to your ancestors.” The kind of listening Moses highlights is the kind that results in appropriate action. If we are to apply God’s word to us, we must remember what it says. And this kind of remembering involves deep, attentive, and obedient attention.

Judaism is an auditory religion. That is why our core credo is, “Sh’ma Yisrael: Listen Israel,” and why the visual, idolatry, is foreign to our ethos. In ancient times, before the Gutenberg press, hearing was the faculty used to take in God’s Word. This is why we so frequently discover the Bible admonishing us to listen, rather than to read!

Life repeatedly teaches us to connect paying attention and remembering. When is the last time you couldn’t find your cell phone, your keys, or your glasses? And why was that? Wasn’t it because you failed to pay attention to where you put them. Yes it was!

Paying attention is essential to remembering. So is repetition, which is likely why our text repeatedly mentions remembering and not forgetting. The repetition is there to prevent us from forgetting and to enable us to remember.

In 8:2 we read, “You are to remember everything of the way in which Adonai led you these forty years in the desert, humbling and testing you in order to know what was in your heart — whether you would obey his mitzvot or not.” Moshe adds, “Think deeply about it” (v. 5). In 8:11 we read “be careful not to forget Adonai your God by not obeying his mitzvot, rulings and regulations that I am giving you today.” So we see here that remembering is an essential means toward obedience, which is what Hashem seeks from us. Being careful, that is, paying attention, is essential to success in remembering.

In verse 19, Moshe reminds us why all of this is important: “If you forget Adonai your God, follow other gods and serve and worship them, I am warning you in advance today that you will certainly perish.”

After all this emphasis on God telling us to remember, it is striking that our haftarah begins this way: “Tziyon says, ‘Adonai has abandoned me, Adonai has forgotten me.’ Can a woman forget her child at the breast, not show pity on the child from her womb? Even if these were to forget, I would not forget you. I have engraved you on the palms of my hands, your walls are always before me.”

Adonai is reporting that his people think he has forgotten them. This indictment against the Holy One is due to the downturn of their fortunes. But he is wrongly indicted. He remembers Israel even more than a woman remembers her child. Our walls are always before him.

For Jews, remembering is holy business. When we remember we bring the past into the present, such that it has the power to stand in judgment over us now.

The past is present in the event that we remember now, and our response to that memory is our response to the event itself and to the saving acts of God.

Each generation of Israel, living in a concrete situation within history, was challenged by God to obedient response through the medium of her tradition. Not a mere subjective reflection, but in the biblical category, a real event as a moment of redemptive time from the past initiated a genuine encounter in the present. (Brevard Childs, Memory and Tradition in Israel)

The events of Israel’s redemption were such significant realizations in history of divine redemptive intervention that, together with the rituals, rites, and commandments they entail, they have the authority to assess each successive generation of Israel, including ours. Our response to these events, rites, rituals, and obligations, is our response to God. And we are accountable. Even though we may wish to avoid this accountability, we cannot.

The Haggadah, echoing the Talmud, agrees. It reminds us, “In every generation a man is bound to regard himself as though he personally had gone forth from Egypt.” Torah tells us of Passover, “This will be a day for you to remember (v’haya hayom hazzeh lachem l’zikkaron)” (Exod 12:14).

The holy past is no mere collection of data to be recalled, but a continuing reality to be honored . . . or desecrated. As a zikkaron, a holy memorial, the redemption from Egypt is so authoritatively present with us at the seder, that a cavalier attitude toward the seder marks as “The Wicked Son,” unworthy of redemption, anyone who fails to accord it due respect. In this remembrance, the holy past is present with power, assessing our response.

That such past-evoking rituals have intrusive and unavoidable authority to judge our response is proven in Paul’s discussion of the Lord’s Table. In First Corinthians 11, he states that those who fail to discern the reality present among them in the ritual of remembrance, who drink the Lord’s cup and eat the bread in an unworthy manner, desecrate the body and blood of the Lord and eat and drink judgment upon themselves. He makes this point unambiguous when he states, “This is why many among you are weak and sick, and some have died” (1 Cor 11:23–31).

Because of this numinous power of holy remembrance, honoring the holy Jewish past and the holy Jewish future as re-presented in the liturgy, ritual, and calendar of our people must become a lived reality in our movement. Our only other option is to dishonor God and to trifle with his saving acts. I think it no exaggeration to say that failure to properly honor our holy past is just as truly an act of desecration as was the failure of the Corinthians to honor the body and blood of Messiah present in their midst in the bread and the wine.

Don’t forget how to remember. It’s serious business.

Scripture references are from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

Two Keys to the Future

God wanted Moses to face the future. We might extrapolate that he expects us to face the future too. Our parasha teaches that facing the future requires two things: Remembering the past, and Listening to, obeying, our God.

Parashat Va-et’chanan, Deuteronomy 3:23–7:11

Dr. Daniel Nessim, Kehillath Tsion, Vancouver

One of the remarkable characteristics of Devarim is that it provides both a retrospective and a prospective view. Speaking to a new generation that did not experience slavery in Egypt, Devarim looks back at what God has done and looks forward to what he will do. For Moses at this late point in his life, there is no discontinuity between the past and the future. He has lived the past. This people whom he is teaching now may not remember it, but to him they are the same people he has been leading for forty years, even though their parents have all died in the intervening years.

Facing Failure

It is an almost irresistible tendency for us to think that we are not like previous generations, and that we can start out afresh without addressing the past. Perhaps that is a good thing, and Moses makes it clear that we are not bound to repeat the mistakes of those who have gone before us. But we have choices to make.

Moses himself wanted to undo the mistakes of his past. He himself recorded his humiliating failure when he struck the rock that God had told him to only speak to, so that God would be magnified before all the people. God told him in Bamidbar (Numbers) 20:12, “Because you did not trust in me, so as to cause me to be regarded as holy by the people of Isra’el, you will not bring this community into the land I have given them.”

Understandably, Moses was distressed. If only he could undo the past! So in 3:25 he asked to cross over and see the land, but God denied him, as he did in our previous parasha. “Rav lecha!” God said, which probably means “too much!” or “let it suffice you,” as Rashi says—“If you keep praying like this you’ll make yourself appear obstinate, and make your master appear too harsh.” Moses had to accept the decree. He wouldn’t get to cross over and see what the other side was like.

Sometimes we would like a preview too. When we are young we might want to know what God wants us to do with our lives. Who to marry? What career to choose? When we get older we might wonder what is on the other side of the river that all must cross someday. “Sufficient for the day is its own trouble,” our great Teacher tells us. “Do not worry about tomorrow” (Matt 6:34). This was a lesson Moses had to accept.

Facing the Future

What God did tell Moses to do, after promising him the opportunity to see the Promised Land from a great distance, was to prepare the next generation. He was to take Joshua and command him, encourage him, and strengthen him. Like Moses we have enough to know, and enough to do, today. Not knowing the future doesn’t mean that we don’t prepare younger generations to face it.

God wanted Moses to face the future. We might extrapolate that he expects us to face the future too. Our parasha teaches that facing the future requires two things: Remembering the past, and Listening to, obeying, our God.

Remembering the Past

Remembering the past has become a trait of our people. In a recent interview Prime Minister Netanyahu emphasized the importance of reading good histories above (not to the exclusion of) any other kind of reading. Through Moses, the nation was told to “be careful, and watch yourselves diligently as long as you live, so that you won’t forget what you saw with your own eyes, so that these things won’t vanish from your hearts” (4:9).

Today we are facing a future full of fears. What will happen to Israel now that the Judiciary’s power is being constricted? Will Israel become a dictatorship? What will happen to us now that Artificial Intelligence has made its big debut? Are we headed for a dystopian future? The Israelites had their fears to face. Will the Canaanites destroy us? How can we face their walled cities? Will we end up living in the desert forever?

The solution to all of these fears and the many others that we face in our lives is to remember the past. In Devarim 4:3 Moses tells them not only to remember, but to identify with the past. To a generation that had never been to Ba’al-P’or Moses says, “You saw with your own eyes what Adonai did at Ba‘al-P‘or.” A few verses later in 4:10 Moses makes it clear that this generation, the one that could claim that the Torah was simply given to the previous generation had themselves “approached and stood at the foot of the mountain.” It was this new generation that Adonai had spoken to out of the fire (4:12) some forty years before. It was this generation to whom Adonai proclaimed his covenant (4:13). “He proclaimed his covenant to you, which he ordered you to obey, the Ten Words; and he wrote them on two stone tablets.”

For Israel, remembering the past was not to be mere memory. It was participation in the past, just as at the Passover Seder each one is to identify with the Exodus as if we had personally been delivered from Egypt.

Hearing the Lord

Facing the future required a second thing. Hearing the Lord.

Variations of the word “listen,” from the root “shema,” occur numerous times in Parashat Va-et’chanan. In 4:1 Moses tells Israel to hear God’s laws and judgments. In 5:1 he again tells them, “Hear O Israel the laws and judgments,” and emphatically adds, “Adonai did not make this covenant with our fathers, but with us—with us, who are all of us here alive today. Adonai spoke with you face to face from the fire on the mountain.” Hearing is now bound up with remembering. The two cannot be separated.

It is this command to “hear” in Devarim 5:1 that prefaces the Ten Commandments. In the Ten Commandments of Deuteronomy, just as in the Ten Commandments of Exodus, the commands begin with the recognition of who God is, a memory, if you will. The first command begins: “I am Adonai your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, where you lived as slaves.” Here the very core of the Torah, the Ten Commandments, is directly connected with the past—the Redemption from Egypt. To face the future, Israel is required to remember what God has done for them in the past, and even more so, to view themselves as personally having been brought out of the land of Egypt.

Having twice told Israel to hear, Moses again tells us—and I think now we should say “us” after learning the lessons about identifying with our people and our common history of redemption—Moses tells us “veshama’ta.” “Veshama’ta” means “and you shall hear.” Once again, this hearing is connected to the past—to the promise of Adonai, the God of [our] ancestors” to give us “a land flowing with milk and honey” (6:3)

Conclusion

And so it is that we are brought to the Shema, in Devarim 6:4: “Hear O Israel, Hashem our God, Hashem is One.” And here is the plot twist.

All of a sudden, after this declaration, in the strongest possible terms, we are commanded to love our God. You shall “love Adonai your God with all your heart, all your being and all your resources” as David Stern of blessed memory translated it. Perhaps because we pray this up to three times a day we forget how revolutionary this command is. So far in the Torah, love for God has only been mentioned twice, and not as a command but as a sort of promise connected to the second of the Ten Commandments. God lavishly bestows “chesed,” or unmerited and kind love toward those who love him.

When we love God, even love him with all of our heart, being, and resources, God’s promise is that he pours out his “chesed” to the thousandth generation.

We remember. We hear God’s commands. Responding to his love, we can have assurance that just as he has always loved us so he will to the thousandth generation. Rashi summarized the Shema and its future ramifications for not just Israel but all peoples by quoting Zephaniah 3:9: “For then I will turn to the peoples a pure language that they may all call upon the name of the Lord,” and again from Zechariah 14:9, “In that day shall the Lord be One and His name One.”

Even so come, Lord Yeshua.

All biblical citations are from Complete Jewish Bible.

Words that Promote Life

Words are essential building blocks for all communication. They can be used for good as well as not-so-good. I believe it is fair to say that words, or d’varim in Hebrew, are necessary to communicating and perhaps even to survival.

Parashat D’varim, Deuteronomy 1:1–3:22

Mary Haller, Tikvat Yisrael, Richmond, VA

Have you ever thought of a world without words?

Words are essential building blocks for all communication. They can be used for good as well as not-so-good. We use words every day to express our thoughts and feelings. Words are necessary to communicate our needs as well as to provide instruction on everything we need to learn for living. Spoken words, written words, sign language and even pictures are representative of words. I believe it is fair to say that words, or d’varim in Hebrew, are necessary to communicating and perhaps even to survival.

If you are a professional communicator, a writer, a philosopher, a rabbi, or an educator of children, words are your livelihood. For human beings words are like food. It would be hard to live without words even for a short period of time. All people, even the most seriously introverted people, use words. Some may only use a few words but the value of words cannot be emphasized enough. Words are clearly essential tools in living life.

Our portion this week is called d’varim in Hebrew or “words” in English. It is particularly striking because all the words Moses speaks throughout the portion are direct, some may even say harsh. Take the verses 6 and 7 of chapter 1 (TLV) “…You have stayed long enough at this mountain. Turn, journey on…”

Perhaps it was simply that Adonai wanted them to move on to receive more of what He had for them. The mountain was a holy place for sure as it was where Moses received the Torah. Yet it was only the beginning. God had promised Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and all their descendants land. Moving on was essential to possessing that promise.

In today’s world, human beings are much the same as they were in the days of Moses. As I see it, we are all flawed; we are curious, yet many of us are fearful of new things, new places, and new challenges. Changing our ways to adapt to new situations or surroundings often comes with challenges we have difficulty overcoming.

Recently my husband and I knew we were to relocate to the Pacific Northwest, affectionately known as the PNW. We both lived on the east coast all our lives, and to make things more challenging, all our married years were spent in the southern portion of the east coast. Needless to say, we were comfortable with our community, our neighborhood, and our friendships. Our dream was to eventually move to a warmer climate. We lived, we served, we prayed, and one day our dreams were challenged. We both knew God had directed us to move.

When the winds of change swept through our lives we had to step out of our familiar territory into the unknown. This was a journey that took everything we had within us to trust that God really had our lives in his hand. We had to overcome waves of feeling fearful and unsure of what was before us. Did God really direct us, did we hear correctly? All the questions that came up had to be faced. We prayed and endeavored to trust that God would continue to honor his words in our journey today as he had done for those who trusted him in Deuteronomy.

Looking back to Exodus 13:21-23 Adonai guided the people with fire by night and protected them with a cloud by day. Moses’s words for the people in our portion of Deuteronomy remind the people of what their God had in store for them. All Moses’s words were important to the people’s progress. Much like the words of the Torah are for us today. The portion closes with a huge reminder of God’s faithful protection in 3:22 when Moses speaks ‘…Adonai your God will fight on your behalf.’

In the last chapter of Deuteronomy we find equally powerful, enduring words of value spoken by Moses to the people that encouraged both my husband and me: “Be strong, be bold, don’t be afraid or be frightened of them, for Adonai your God is going with you. He will never fail you or abandon you” (Deut 31:6–8 CJB).

Moses said God would be with his people, and would protect them from any giants in the land. Perhaps our giants were not literal giants, but rather all the big things that are out of our human control.

We sold our home. Then came the thoughts, what if we made a mistake? Were Yeshua’s words in the Matthew 6:25 “So I say to you do not worry about your life” really true? Would our God provide for us? We stepped out and God’s faithfulness proved to be true.

Our journey in the PNW continues. Each day presents with new opportunities as well as new solutions. Each day our trust grows. We understand more clearly that our God is truly with us.

The words or D’varim spoken by Moses continue to hold current value for individuals as well as for communities.

In 1849 the French writer Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karl first wrote “plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose,” which translated roughly means, “the more things change the more they stay the same.” This quote seems fitting as I continue to ponder the words of this Torah portion.

The intimate relationship between Adonai and Moses fueled Moses’ fire to invest his all for a people who, like many of us today, struggle with trusting a God that cannot be seen with our physical eyes. The words spoken by Moses born out of his trusting relationship prove to be timeless wise words of value that promote life.

It is my hope that the words of Moses have encouraged you as they have encouraged me. Always remember to invest wise words that express faith, truth, and kindness for the generations to come. Adonai is the same yesterday, today, and on into the future.

The Virtue of Transparency

One of the more common critiques leveled against the Bible is that it does not fairly adjudicate in the battle of the sexes. When we remove the lens of 21st century modernity, however, we can see in this week’s reading several key Jewish principles that govern familial and authoritative relationships.

Photo: The Times of Israel

Parashat Mattot-Masei, Numbers 30:1–36:13

Matthew Absolon, Beth Tfilah, Hollywood, FL

Any vow and any binding oath to afflict herself, her husband may establish, or her husband may make void. . . . But if he makes them null and void after he has heard of them, then he shall bear her iniquity. (Numbers 30:13, 15)

One of the more common critiques leveled against the Bible is that it does not fairly adjudicate in the battle of the sexes. A casual reading of this week's portion might incite the reader to such a conclusion. When we remove the lens of 21st century modernity, however, we begin to see several key Jewish principles that govern familial and authoritative relationships. Indeed, the nature of our Father in heaven is illuminated for our benefit.

In Numbers 30 we see several important guiderails that mark the importance of personal responsibility, transparency, and respect for authority within the Jewish home. God outlines for Moses the responsibility of the father and, in the case of marriage, the responsibility of the husband, to affirm or nullify vows made to the Lord, specifically, vows made by a daughter or a wife. At the close of the chapter, we catch an insight as to why God places this authority on the father of the home. It is because God holds the father responsible for the spiritual deeds and misdeeds of his household.

Rambam in his commentary on Numbers 30:15 says the following:

It would appear that this woman [broke her vow] in error or was misled, for Scripture speaks [here] of a husband who heard [his wife’s vow and did not annul it on that day], and the wife does not know about this, and after some time he “annulled” [the vow, although he in fact no longer had the power to do so], and told her that [he annulled it] in the day he heard it. Thus Scripture teaches us two things: that the husband bears her iniquity as if he had made a vow and profaned his word, and that she is totally free and not liable to any of the punishments [found elsewhere] for errors. . .Scripture speaks of normal circumstances, that a father usually guards himself against doing this because of his love for his daughter, whereas a husband might perhaps hate his wife and think that he will make her guilty [by misleading her to break her vow].

In short, there is an underlying godly virtue at play between the father and the daughter, and the husband and the wife. That virtue is respect of spiritual agency through integrity and mutual transparency. Unlike the pagan nations who treated their women as property and therefore without spiritual agency, the Torah elevates our women to a place of personal spiritual agency before the Lord. Even more so, it lays the burden upon the father and husband to honestly and righteously cultivate the spiritual agency of our daughters and wives. It requires the men to be hands-on.

Building upon that theme, it becomes clear that mutual transparency is a preeminent virtue inside a healthy family dynamic. The Torah presupposes the integrity of motive of our daughters and wives, while safeguarding against the possible abuses of an overbearing or ungodly head of the house. In a healthy, godly Jewish home, the father is hands-on in the spiritual life of his wife and daughters. Out of respect for that responsibility, the Torah is encouraging that there be transparency between the two parties; transparency from the daughter/wife to the father/husband out of respect for the burden of spiritual responsibility over the house; and transparency and integrity from the father/husband towards his daughter/wife out of respect to the spiritual agency that God has given them. In other words, as far as a healthy family dynamic is concerned, we’re all in this together.

In the following chapter we see an example of God exhibiting this same level of transparency towards us, his chosen bride. After the plunder of the Midianites, a tribute was taken “to the Lord” (Num 31:29) to be used in the service of the Mishkan. Not only was this tribute clearly outlined with specific percentages applied to specific assets, but also the actual quantity of tribute that was proportioned to the Lord was publicly recorded, down to the very last animal.

The question remains, what compels the God of the universe to show transparency to those he created from the dust of the earth? What lesson for posterity is to be found in this chronicle of “open book accounting”?

One answer is that God is exhibiting for us his nature so that in turn, we may embody his virtues. Regardless of one's station of authority, within the family of God transparency is always the right path towards healthy and respectful relationships. Moreover, in the same way that God spelled out the terms of transparency before us, so too we should invite and welcome terms of transparency in our positions of leadership.

In reflection, the Torah expects a hands-on approach from husbands and fathers towards the spiritual growth of our daughters and wives. This hands-on duty requires transparency and integrity of motive between the family members. Moreover, it places the burden of responsibility upon the father to nurture the spiritual agency of his daughter with love and wisdom; and to honor the spiritual agency of our wives with respect and partnership. And finally, our Father himself demonstrates for us that Godly authority can only be fully exercised within the virtues of integrity and mutual transparency, and that those in positions of authority should welcome and embrace the terms that hold them to account.

Unexpected Words from the Wise

Seven things distinguish a fool and seven things distinguish a wise person. . . . If there is something the wise person has not heard, the wise person says, “I have never heard.” The wise person acknowledges what is true. The opposite of all these qualities is found in a fool. (Pirke Avot 5:9)

Parashat Pinchas, Numbers 25:10–30:1

Rabbi Russ Resnik

Seven things distinguish a fool and seven things distinguish a wise person. The wise person does not speak in the presence of one who is wiser. The wise person does not interrupt when another is speaking. The wise person is not in a hurry to answer. The wise person asks according to the subject and answers according to the Law. The wise person speaks about the first matter first and the last matter last. If there is something the wise person has not heard, the wise person says, “I have never heard.” The wise person acknowledges what is true. The opposite of all these qualities is found in a fool. Pirke Avot 5:9

Three times in the narrative of Torah, the Israelites encounter legal cases not directly covered by the statues and ordinances they have recently received from God. The cases involve a blasphemer (Lev 24:10–22), some men who were ritually unclean at the time of the Passover sacrifice (Num 9:6–14), and a violator of Shabbat (Num 15:32–36). Each time when the people ask Moses for a ruling, he must answer “I have never heard,” until the Lord gives him additional instructions. Now, in Parashat Pinchas, a fourth case comes before Moses.

Zelophehad, of the tribe of Manasseh, has died leaving no heir—that is, leaving no son. His surviving daughters, however, appeal to Moses. As women, they cannot inherit land directly, and so they are concerned that their father’s name and inheritance among the tribes will be lost to his family forever. Accordingly, they make their request: “Give us a possession among our father’s brothers” (Num 27:4). Moses seeks the Lord, who rules in favor of the daughters, and against the patriarchal assumption of the times, thus adding a new instruction to Torah: “If a man dies and has no son, then you shall cause his inheritance to pass to his daughter” (Num. 27:8).

Moses fulfills the description of the “wise person” in the quote above from Pirke Avot. When he does not know, he says “I do not know.”

One midrashic tradition praises Moses since he thereby taught “the heads of the Sanhedrin of Israel that were destined to arise after him, that … they should not be embarrassed to ask for assistance in cases too difficult for them. For even Moses, who was Master of Israel, had to say, ‘I have not understood.’ Therefore Moses brought their cases before the Lord.” (Jacob Milgrom, Numbers, The JPS Torah Commentary, citing Targum Jonathan)

The ability to admit “I have not heard; I do not know” is rare among leaders, especially in our day of spin and talking points. It seems to be an unspoken rule of politics that you don’t admit mistakes, and you don’t say “I don’t know”—even when you don’t know! How refreshing it would be today to see those in power simply admit their mistakes and acknowledge the gaps in their knowledge.

The Psalmist says “The Torah of the Lord is perfect” (Psa 19:7 [8]). A thousand years later, Paul writes, “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, thoroughly equipped for every good work” (2 Tim 3:16–17). But Scripture’s perfection, its ability to make us complete and thoroughly equipped, does not mean that it spells out everything in detail. Sometimes it directs us back to the Lord for more instruction, or to another provision laid down toward the end of the Torah:

If a matter arises which is too hard for you to judge . . . then you shall arise and go up to the place which the Lord your God chooses. And you shall come to the priests, the Levites, and to the judge there in those days, and inquire of them; they shall pronounce upon you the sentence of judgment. (Deut 17:8–9)

Traditional Judaism often cites these verses as a basis for the Oral Torah, rabbinic teachings and interpretations not found in the written Torah but seen as essential to properly applying it in the various times and places of the Jewish story. This tradition sees the Torah—written and oral—as given once for all, but discovered anew in every generation through discussion and friendly argument. Students in yeshiva, a Jewish school for Torah study, continue to study in this manner today.

To an outsider this method of study can appear chaotic. Each pair works at its own pace; everyone is talking out loud; boys are constantly jumping up to find books or consult with other students; people come and go seemingly at random. But that’s how yeshiva students have been learning for centuries. (Sue Fishkoff, The Rebbe’s Army: Inside the World of Chabad-Lubavitch)

In the case of the daughters of Zelophehad, of course, the answer comes not through study and debate, but through an oracle of God. Nevertheless, their story establishes a truth that remains vital for us. God’s word does not address every specific circumstance we will encounter in life, but it provides all the direction that we need. A wise student of Scripture must sometimes say “I have not heard; I do not know” and seek to learn more.

Thus, right after Paul tells Timothy that Scripture equips completely, he charges him, “Preach the word! Be ready in season and out of season. Convince, rebuke, exhort, with all longsuffering and teaching” (2 Tim 4:2). Scripture itself ordains teaching, study, exhortation as the means of revealing all that it has to offer.

As we consider these general applications of the story, however, we should not overlook the specific ruling regarding the daughters of Zelophehad, for it echoes the theme of restoration that sounds throughout Torah.

The twelve tribes are about to enter the Promised Land, where each is to receive a divine allotment, but sin has broken into the story again. Zelophehad “died in his own sin,” according to his daughters, leaving no heir (Num 27:3). The daughters probably don’t mean to say that their father was an exceptional sinner, but simply that his life, like all lives, was tainted by sin. Regardless, the division of the land is disrupted, and divine order is threatened. But God takes action to restore the wholeness of the land and people of Israel. What is most striking here is that he does so through the daughters, those who normally are marginalized. Women are generally subject to men in the Mosaic legislation, but God reveals that they are able to inherit, to bear the family name, and to preserve the legacy. God’s ruling in this case reminds us that he originally created woman out of man, not to be subservient, but to be “a sustainer beside him” (Gen 2:18 Alter).

Here again the grand narrative of Torah moves forward not on the limited insight of human actors, who often must say, “I don’t know,” but on the boundless wisdom of God, wisdom we access when we recognize that our own wisdom comes up short.

Adapted from Creation to Completion: A Guide to Life’s Journey from the Five Books of Moses. Messianic Jewish Publishers and Resources.

Scripture references are NKJV.

Father Knows Best and Pin the Tale on the Donkey

As I read the Scriptures, I’m struck by how much of it relates to my childhood in the 50s and 60s. The TV show “Father Knows Best” and the game of “Pin the Tail on the Donkey” come to mind. In this week’s double portion, however, it’s a tale that the donkey realizes first.

Parashat Chukat-Balak, Numbers 19:1–25:9

Suzy Linett, Devar Shalom, Ontario, CA

As I read the Scriptures, I’m struck by how much of it easily relates to my childhood in the 50s and 60s. The TV show “Father Knows Best” and the childhood game of “Pin the Tail on the Donkey” come to mind. In this week’s double portion, however, it is a tale—one of deception, rebellion, and the need for obedience—that the donkey realizes first.

The reading opens after the rebellion of Korach when he was swallowed by the earth; followed by ongoing complaints, the need for repentance, and further consecration of the tithes and offerings. This week, the reading begins in Numbers 19 with a list of rules directly from the Lord which are difficult to comprehend, but nonetheless required. Those who were contaminated by touching the dead bodies during the rebellion must be purified. The purification comes through the sacrifice of a red heifer, with many specific qualifications. The Israelites are to follow them in order to return to the Lord’s presence. Despite the meticulous and tedious tasks, it is not long until, following the death of Miryam, the people once more rebel against Moses and Aharon.

All this reminds me of that television series. Each week, a problem or difficulty was presented to Jim Anderson, the father of the family. It was resolved with the realization that the father of the house had the answer, had the solution, and expected certain specific behaviors. Yet, in the following episode a week later, a different problem ensued with the same outcome and resolution.

Why didn’t the children of Israel learn? Why didn’t the Anderson family learn from week to week on television? Why do we fail to follow our Heavenly Father’s commands and statutes fully? As I struggle with this failure and with my personal desire to do right versus my fleshly inclinations, I am drawn to compassion. I see the reality of the struggle. I have the entirety of the Word of God, I have the indwelling presence of Ruach HaKodesh, and I have the truth of Messiah, yet I blow it. I fail.

When the Israelites lacked water, Moses was to speak to the rock once again, yet this time he struck it (Num 20:7–11). He was tired of the constant whining, of the moral failures of the people to follow the statutes, completely. He was frustrated. Those of us in ministry leadership understand. Sometimes the members of our congregations complain. They fail to follow the teaching. Yet, for Moses, his act of defiance kept him from entering the Land of Promise (Num 20:12). Why did such a simple failure result in such a tremendous act of discipline? Scripture says, “From everyone given much, much will be required” (Luke 12:48 b). Moses was in a position of leadership and had been given the nation. He had wealth and power. He had fame. He failed and, as a result, much was required of him. Great discipline was required for the people to understand that everyone must follow the Lord. The leadership is not exempt.

The Israelites continue their march. Esau/Edom provides a difficulty, but as always, the Lord prevails (Num 20:18–21). Aharon dies and his son assumes the priesthood (20:27–29). The Israelites are victorious over Og and Sichon (21:34–35). They enter the area of Moab and reach the banks of the Jordan, and Moses is able to view the Promised Land before he dies, showing the compassion of the Lord through the disciplinary process (27:12).

The question for the Israelites and for us today is whether or not we understand that our Heavenly Father really does know best. This is like another childhood experience I believe many of us had when we questioned our parents’ authority: “Because I’m the father/mother, and I said so! That’s why.” We are commanded to follow the instructions even when they don’t make sense to us. The blood of a red heifer should not cleanse or purify anyone from a medical standpoint. Speaking to a rock, or even striking it, should not bring out gushing water from any scientific view. Further in the passage, a bronze serpent is lifted up to save the people from poisonous snakes. There is no medical or other logic here. Yet, later, in following passages, the people will fail and begin to worship the bronze serpent. Yeshua will refer to it in John 3:15. Will the Israelites walk in obedience? Will we walk that way when life doesn’t make sense?

The next parasha in our pair continues the story. Balak, King of the Moabites, unites with the Midianites to fight and destroy Israel. He hires the prophet Balaam as a hitman to pronounce a curse upon the Israelites so that they may be defeated in battle. The prophet is instructed by the Lord that he is not to go with Balak, and not to pronounce curses, as the Israelites are blessed, but to say what he is told (Num 22:18–20). Balaam struggles with the need to bless Israel and yet wants the vast sums of money offered to speak curses. He saddles his donkey and heads out. The angel of the Lord blocks the path. The donkey sees the angel and stops. After a few exchanges, the donkey speaks to Balaam. This is where it gets interesting. I am an animal lover. Yet if my pets, or any animal, were to speak to me in English, I believe I would pass out. Not Balaam. He begins to argue with the donkey. I argue with myself. I know what I should or shouldn’t do, yet I struggle. Paul says the same thing centuries later: “For I do not understand what I am doing—for what I do not want, this I practice, but what I hate, this I do” (Rom 7:15). The struggle is real. Do we accept our personal accountability, or do we argue and attempt to “pin the tail,” or the tale of the circumstances, on the donkey or other speaker of truth?

Humility requires that we accept correction from others, often those who we may see as having less spiritual understanding or ministry training. Do we accept it, or see those who oppose us as donkeys? Balaam accepted the correction after the argument, and pronounced the blessing of Ma Tovu: “How lovely are your tents, O Jacob, and your dwellings, O Israel!” (Num 24:5), which becomes such an integral part of Jewish morning liturgy. Balaam follows with another blessing, prophesying the coming of the Jewish Messiah (24:17). Yet sin continues, and as the Torah reveals, Israel persists in a cycle of commitment, failure, repentance, and return to God.

Our Heavenly Father does know best, and sometimes we must check to see if we are playing pin that tale on the donkey.

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

Overcoming Betrayal

One can only wonder what it must have been like for Moses to be challenged with open mutiny by the very people he called friends. Did this betrayal take Moses by surprise?

Parashat Korach, Numbers 16:1–18:32

Matthew Absolon, Beth Tfilah, Hollywood, FL

Now Korah the son of Izhar, son of Kohath, son of Levi, and Dathan and Abiram the sons of Eliab, and On the son of Peleth, sons of Reuben, took men. And they rose up before Moses, with a number of the people of Israel, 250 chiefs of the congregation, chosen from the assembly, well-known men. They assembled themselves together against Moses and against Aaron and said to them, “You have gone too far! For all in the congregation are holy, every one of them, and the Lord is among them. Why then do you exalt yourselves above the assembly of the Lord?” (Num 16:1–3)

How unsettling it must have been for Moses to see this group of distinguished leaders walking towards him with defiance in their eyes. One can only wonder what it must’ve been like for Moses to be challenged with open mutiny by the very people he called friends. Did this betrayal take Moses by surprise?

There is an unfortunate tendency amongst the children of God to squabble and to fight amongst ourselves. This fratricide is not unique to the Jewish people. It is endemic to the human experience. Selfish ambition, pride, vainglory, and oftentimes outright jealousy are diseases for which there is no eradicating vaccine.

There are many victims in times like this. The individual members of the community, the family members and associates looking on, and perhaps the most misunderstood of all is the very leader against whom the mutiny is directed. Betrayal and mutiny are traumatic events in the growth cycle of every leader.

In our reading of the text it is critical that we do not sanitize its human reality. Korach and Abiram were not Moses’s enemies. They were co-leaders with Moses, “well known men.” Moses would have known them personally. He knew their wives. He knew their sons and daughters. He celebrated with them at the birth of their grandchildren. These people are not “others,” they are not “them over there.” They are our people, God’s people, Moses’s flesh and blood brothers.

One can only imagine the heartbreak that Moses must have endured as he watched the fallout and collateral damage that resulted in the actions from a handful of vainglorious men. The wives. The children. The grandchildren. All gone in a moment of ghastly horror.

It is clear that the text wants us to know that Moses was angry with Korach and his revolutionaries. It even leaves us a transcript of Moses’s conversation with the Lord: “Do not respect their offering. I have not taken one donkey from them, and I have not harmed one of them” (16:15). But unlike the despotic kings who were to follow (such as Ahab and Herod), Moses did not allow his anger towards a handful of men to harden his love for God’s people.

In verse 22 we see the heart of Moses come bursting forth in what is clearly a test from the Lord, who threatens to consume the whole congregation (Num 16:20–21). “O God, the God of the spirits of all flesh, shall one man sin, and will you be angry with all the congregation?” Moses loved God’s people. Moreover, he did not allow the sharp pain of betrayal to fan the flames of bitterness towards others.

This test upon Moses echoes a similar conversation between God and our father Abraham in Genesis 18. God says “shall I hide from Abraham what I am about to do?” (Gen 18:17). Or HaChaim astutely points out that the people of Sodom whom God is going to destroy are the same people who Abraham rescued in the matter of Lot’s captivity (Gen 14). The heart of Abraham our father is tested to see if he has the attribute of divine mercy, by seeking the salvation of a people he rescued, despite the cry of their violent sins against God and their persecution against Lot.

And so we see this parallel with Moses, the savior of Israel. Moses is given every good reason for God to execute justice upon our forefathers, but he responds with the same heart of Abraham, petitioning for God’s mercy to triumph over his justice.

Nor did Moses allow betrayal to cause resentment for his calling. After all, Moses is the common denominator. And it is the calling of the Lord upon Moses’s life that is being challenged. As Moses unequivocally deduces, “Therefore it is against the Lord that you and all your company have gathered together.”

In the course of this one dreadful day Moses was the victim of slander and character assassination; his innocent brother was attacked; his relationship with God was called into question; his God-ordained calling was publicly challenged; he was accused of despotism; he was accused of nepotism; he was accused of narcissism.

Yet we see Moses respond with two overarching virtues: first, his love for the people of God. And second, he remained faithful to his calling. Despite the lies that were cleverly crafted about him, he held fast to God’s unfailing love and his unerring truth. The great Leo Tolstoy comments to this end: “The sole meaning of life is to serve humanity by contributing to the establishment of the kingdom of God, which can only be done by the recognition and profession of the truth by every man” (Leo Tolstoy, The Kingdom of God Is Within You).

Moses was judged unfairly by men who were filled with a vision from the devil instead of a vision from God. Moses’s response offers to us a blueprint and a meditation on the qualities we should strive for in godly leadership—that despite the deep hurt of betrayal, and its accompanying anger, we must always maintain love for God’s people and faithfulness to God’s calling in our lives.

Scripture references are from the English Standard Version (ESV).